Co-Employment & Worker Misclassification Risks in Staff Augmentation: What Tech Leaders Need to Know

Let’s imagine a simple scenario. A company scales its development capacity fast, hiring augmented engineers across borders and blending internal and external teams into one agile unit. The approach works smoothly until an audit uncovers an uncomfortable truth: some of those “contractors” may legally be employees. Overnight, efficient scaling becomes a liability line item.

Worker misclassification is one of the most expensive compliance traps facing global tech organizations today. Regulators are coordinating enforcement across borders, and penalties are rising, not only in the U.S. and EU but also in Asia and Latin America, where cross-border teams are increasingly common.

But the problem isn’t intent. Most companies simply apply the same vendor logic everywhere, assuming the contract defines the relationship. Regulators focus on control, dependency, and how work is actually managed. That’s where co-employment in staff augmentation legal risks begin: when what happens operationally doesn’t match what’s written on paper.

In our previous blog post, we explored how co-employment in outstaffing arises and why IP ownership becomes critical in augmented arrangements. With this article, we go beyond definitions to examine co-employment and misclassification risks in staff augmentation, their costs, and how to prevent them without slowing delivery.

What global worker misclassification means in staff augmentation

Worker misclassification in IT staffing occurs when a person engaged as an independent contractor or vendor employee effectively operates as a company employee in practice. In staff augmentation, this often overlaps with co-employment, where both the client and the vendor exercise elements of control, such as supervision, scheduling, or integration into internal workflows.

When that boundary blurs, regulators may view the setup as disguised employment or shared employer liability, exposing both parties to payroll taxes, benefit obligations, and compliance penalties. In many jurisdictions, the client company is still treated as the economic employer, even when external specialists are formally employed by an IT vendor.

Worker misclassification in staff augmentation

Why staff augmentation is prone to it. The staff augmentation model sits in a gray zone between independence and employment. Developers join internal channels, attend company meetings, and often work exclusively for a single client over long periods. While this operational overlap improves speed and alignment, it also blurs legal boundaries and creates an inherent tension: the model works best when augmented staff integrate deeply, yet that same integration is what triggers co-employment and worker misclassification risks.

When day-to-day control, supervision, or tool access resembles employment, regulators may view the setup as either misclassification or co-employment in IT staffing, where both the client and the vendor share employer obligations. In both cases, the issue isn’t what the contract says, but how the relationship functions in practice.

Signs you may fall under employee misclassification

No single factor determines employment status. Regulators weigh the total picture of how work is performed, and the same signals can help you self-assess before problems arise.

If several of these apply, your engagement may need restructuring or stronger documentation to avoid co-employment and misclassification risks in staff augmentation:

- Control and supervision. External engineers receive detailed daily direction on how to perform tasks, join sprint reviews, or have performance goals set by your internal managers.

- Tooling and access. They use your internal email, repositories, CI/CD systems, and Slack channels like any full-time employee.

- Integration and visibility. Augmented specialists appear in your organizational chart or internal directories and are introduced to others as part of the company.

- Duration and exclusivity. They work full-time for extended periods with no defined project end or rotation.

- Economic dependency. The developer has no other clients and bills solely through one vendor or platform.

- Training and performance oversight. External engineers join internal onboarding, receive skill training, or get performance reviews from your managers. These actions suggest integration into your HR processes and can indicate employee-style supervision.

- Access to benefits or direct termination rights. If augmented specialists receive company perks, bonuses, or can be dismissed directly by your managers instead of through the IT vendor, regulators see that as employer control.

When this level of integration occurs, contracts alone may not be enough to protect you. Thus, if day-to-day reality looks like employment for regulators, they will treat it as such.

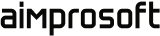

The cost of misclassification

Misclassification doesn’t just result in a legal adjustment; it can trigger a chain of operational and financial consequences:

- Financial: retroactive payroll taxes, unpaid benefits, and penalties for misreported employment.

- Operational: delayed payments, disrupted audits, and paused M&A transactions until compliance risks are resolved.

- Strategic: uncertainty over intellectual property ownership if misclassified workers didn’t properly transfer rights.

These risks often emerge months or years later, usually during financial audits or due diligence, when investor teams trace every contractual detail back to actual work practices.

Real-world examples

These aren’t abstract scenarios. Enforcement around worker classification has intensified globally, especially in technology-related sectors where flexible work models are common.

- Microsoft permatemp case

In one of the most cited staff augmentation misclassification cases, Microsoft used long-term contractors through staffing agencies for years. The court found that those workers were effectively employees due to direct supervision, integration into teams, and long-term continuity. The company settled for $97 million and overhauled its contractor management policies. - Google and Cognizant joint-employer ruling

In 2024, the U.S. National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled that Google and Cognizant were joint employers of YouTube Music contract workers supplied through Cognizant. The decision came after contractors argued they were directed and managed by Google staff while formally employed by Cognizant. The case reignited debate about co-employment in outsourcing and tech vendor models, illustrating how shared supervision and control can expose both companies to joint liability for labor rights and compliance obligations.

The principle is always the same: if a company directs how, when, and where someone works, authorities tend to view that person as an employee. The tech industry faces particular scrutiny compared to other sectors because remote work, global teams, and digital tooling make deep integration easy and visible. Unlike industries where contractors work on-site with physical separation, software development leaves digital trails (commit logs, Slack history, calendar invites) that regulators use as evidence of control and supervision.

Global worker misclassification isn’t always the result of negligence. Instead, it’s often the byproduct of operational convenience and global scaling. But when structure and documentation lag behind day-to-day reality, the staff augmentation legal risks compound quietly until regulators or auditors uncover them.

In the next section, we’ll look at how regulators across regions determine employment status and what legal frameworks, from the U.S. Common Law test to the EU’s subordination model, shape these decisions.

How regulators determine employment status

Every country defines employment differently, but most rely on a mix of control and dependency indicators. These are often called tests: sets of criteria that regulators use to decide whether someone labeled a contractor or vendor resource should legally be treated as an employee.

While the details vary, they all focus on the same underlying question: who controls how, when, and where the work is done, and who bears the economic risk. Regulators look at how collaboration unfolds in practice:

- Who directs daily priorities?

- Who provides tools, workspace, or credentials?

- Can the person work for other clients simultaneously?

- Is payment tied to time or deliverables?

- Does the person bear financial risk or opportunity for profit beyond hourly rates?

If the answers suggest dependence and control, misclassification is likely, regardless of the contract wording.

| Region | Primary test or principle | What regulators focus on | Typical triggers for employment status |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Common Law Test (IRS) and Economic Reality Test (DOL) | Degree of control, financial relationship, and nature of engagement. | Daily supervision, inability to negotiate rates or terms, or long-term exclusive integration into client systems. |

| European Union | Subordination & Integration Principle (applied differently across member states; France and Germany maintain particularly strict subordination standards). | Whether the worker operates under the client’s authority and within its structure. | Reporting lines, use of internal tools, and participation in company routines. |

| United Kingdom | IR35 Test | Control, personal service requirement, mutuality of obligation, and right of substitution. | Fixed working hours, direct supervision, or inability to send a substitute. |

| India | Contract Labour Act & EPF/ESI Obligations | Whether the worker operates an independent business with multiple clients and proper registrations (PAN, GST). | Exclusive long-term engagement, use of the client’s premises/equipment, and absence of business registration or invoicing through a registered entity. |

| Latin America (varies by country) | Economic Dependence & Social Security Registration | Who provides tools and sets schedules, whether the worker has local business registration and multiple clients. | Exclusive long-term engagement, use of client equipment/facilities, and absence of local entity or social security registration. |

What these tests mean in practice

For companies using staff augmentation across borders, these frameworks share one core message: regulators care about behavior, not paperwork. A contract may label someone as a contractor, but if their work life mirrors that of an employee (integrated, directed, and dependent), classification will follow that reality.

These tests continue to evolve, often in ways that directly affect how cross-border tech teams are managed.

- In the U.S., the Department of Labor’s 2024 rule re-emphasized the totality of circumstances approach, replacing the more contractor-friendly 2021 standard (note: this rule faces ongoing legal challenges).

- In the UK, IR35 enforcement expanded to medium and large private sector organizations in 2021, shifting liability for incorrect classification to the hiring company.

- In France and Germany, courts have increasingly reclassified long-term IT contractors as employees when they work exclusively for one client, use client systems extensively, and lack genuine operational independence, extending employment scrutiny to distributed technical teams.

- Across India and Latin America, labor and tax authorities increasingly share information, scrutinizing repeated long-term engagements without proper local entity structure as potential employment relationships.

Across all jurisdictions, the same principle applies: if you control the work like an employer, you’ll be treated like one. The safest approach isn’t to memorize every local test but to build engagement structures that can pass all of them: clear scopes, time-bound projects, independent delivery, and documented boundaries. For high-risk jurisdictions or large-scale engagements, local legal counsel should validate classification before work begins.

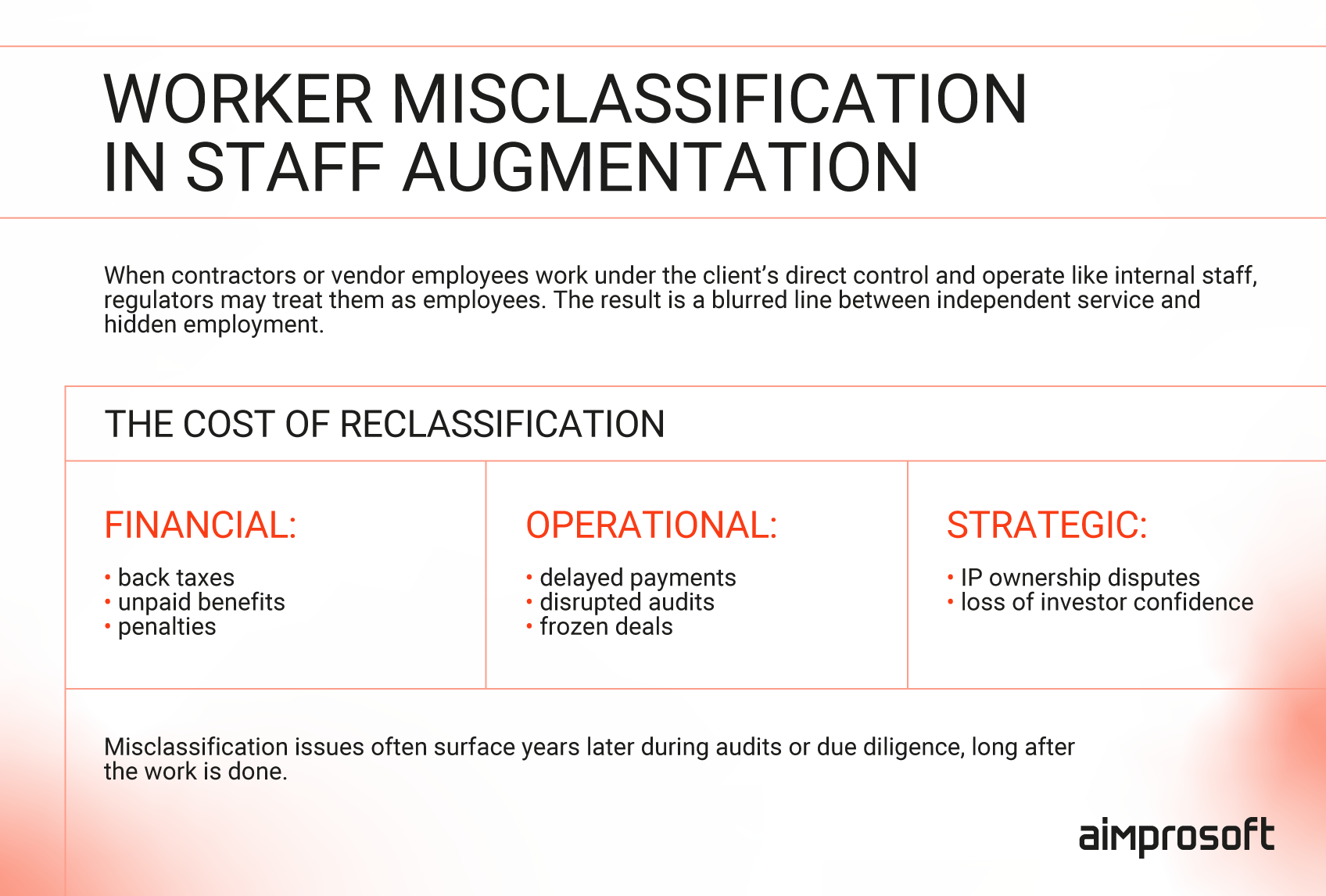

The business impact of misclassification

Once worker status comes under regulatory scrutiny, the fallout rarely stays confined to legal fees. Misclassification affects how teams deliver, how investors perceive the company, and how financial stability is maintained. Even a single audit can slow development cycles, freeze budgets, and erode trust with clients and partners.

Risks of employee misclassification

Financial exposure

Retroactive tax and benefit liabilities

When external workers are misclassified as employees, companies become responsible for all payroll taxes that should have been withheld. This often includes income tax, social contributions, health insurance, and pension payments. The totals are rarely small; auditors usually apply interest and late-payment penalties that multiply the original amount.

Legal and settlement costs

Defending against misclassification findings can require specialized legal counsel, third-party audits, and negotiations with multiple agencies. Even when settlements are reached, companies may still need to reimburse affected workers for lost benefits or overtime.

Long-term financial uncertainty

Unresolved classification disputes can appear as contingent liabilities on financial statements. That affects valuation and complicates investor discussions, especially during funding rounds or acquisitions.

Operational disruption

Project delays and halted releases

Misclassification reviews can freeze budgets and disrupt delivery schedules. Payment flows are often paused until compliance checks finish, leaving teams idle and milestones missed.

Administrative overhead

Once a company faces an investigation, every engagement must be re-verified. HR, finance, and legal teams spend weeks gathering contracts, invoices, and onboarding records to prove independence. The process slows decision-making and diverts focus from growth to remediation.

Dependency risk

If the vendor under investigation employs several key engineers, those workers might have to be reassigned or temporarily suspended. Projects that rely on their expertise can stall without immediate replacements.

Reputational and strategic risk

Investor and client perception

Reclassification cases can create an image of weak governance. Even if the issue stems from administrative oversight, external stakeholders often interpret it as non-compliance or poor control over global operations.

Talent retention challenges

Developers and partners value legal stability. Once a company becomes known for compliance problems, attracting top independent specialists becomes harder. Vendors may also raise rates to compensate for perceived risk.

Impact on mergers and acquisitions

Misclassification findings frequently appear during due diligence. Potential buyers or investors may demand escrowed funds to cover possible liabilities or lower the company’s valuation to offset legal uncertainty.

Misclassification doesn’t always make headlines, but its internal consequences are long-lasting. Financial exposure, delivery slowdowns, and reputational strain can undermine even well-managed companies. The next section explains how to prevent these outcomes by identifying the most common triggers of misclassification of employees before they escalate into liability.

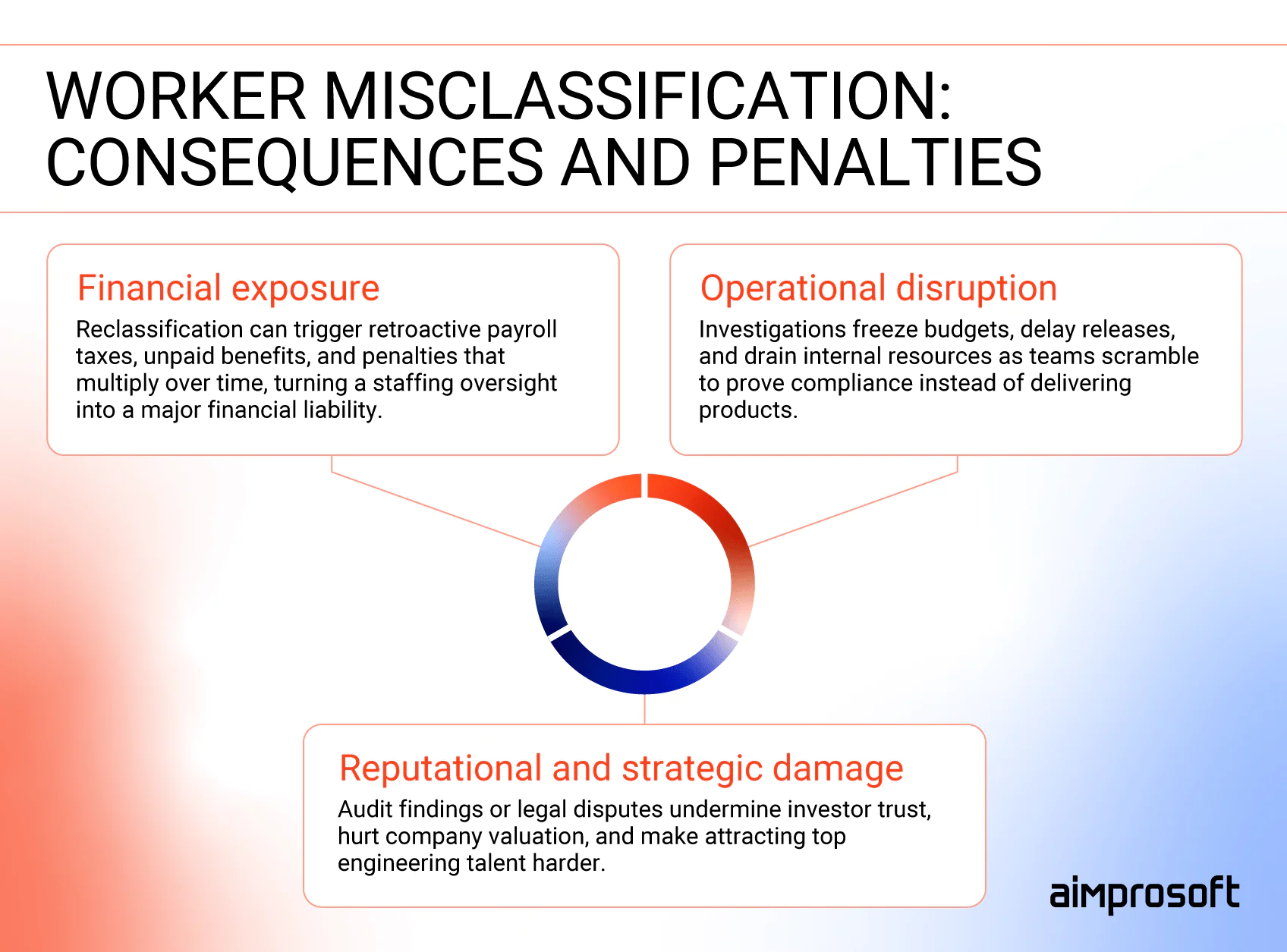

Common triggers for worker misclassification in tech outstaffing

Misclassification rarely stems from a single mistake. It’s usually a series of operational patterns that blur the legal boundaries of co-employment and worker classification. When day-to-day work starts resembling internal employment (shared tools, direct management, or indefinite engagement), regulators may treat the arrangement as hidden employment or even co-employment in outstaffing, where both you and the vendor share liability.

Common triggers for employee misclassification

1. Long-term engagement without a defined endpoint

When a contractor or vendor-supplied developer works full-time for years on ongoing tasks, the relationship starts to resemble permanent employment. Regulators see duration and continuity as signs of dependency, especially when there’s no rotation of resources or a clear project-based conclusion.

2. Direct supervision and participation in daily operations

If augmented engineers attend internal stand-ups, receive performance feedback, and have priorities set by your managers, the balance of control shifts. These are exactly the conditions where the co-employment vs contractor distinction becomes critical; regulators may interpret such involvement as evidence of employment, not independent service.

3. Access to internal tools and systems

Using company email addresses, credentials, or HR systems makes external workers appear fully integrated. Shared repositories and communication channels further blur independence and reinforce the impression of internal employment.

4. Lack of independent invoicing or business structure

True contractors operate as separate business entities, issuing invoices, paying taxes, and serving multiple clients. When individuals work solely through a vendor without their own registration or financial autonomy, auditors often conclude that you, as a client, exert de facto control over employment conditions.

5. Contract terms that don’t match reality

Many setups appear compliant on paper but fail in practice when operational realities contradict the signed agreement. If a contract labels a role as “independent,” yet the worker is supervised, follows fixed schedules, or performs exclusive tasks, regulators interpret that inconsistency as evidence of misclassification.

None of these factors alone define employment. Regulators assess the full picture (control, dependency, and integration) to determine whether the relationship is truly independent or simply labeled that way. The stronger these co-employment patterns become, the harder it is for you to prove that your contractors or vendor staff are genuinely separate from internal teams.

Work with a partner who treats compliance as seriously as delivery. Let’s build an augmentation model that scales safely, without the risk of misclassification.

Understanding these triggers is the first step toward prevention. In the following section, we’ll explore how to structure staff augmentation contracts and how to avoid co-employment in IT staffing and employee misclassification so that you can keep staff augmentation agile while staying within compliance boundaries.

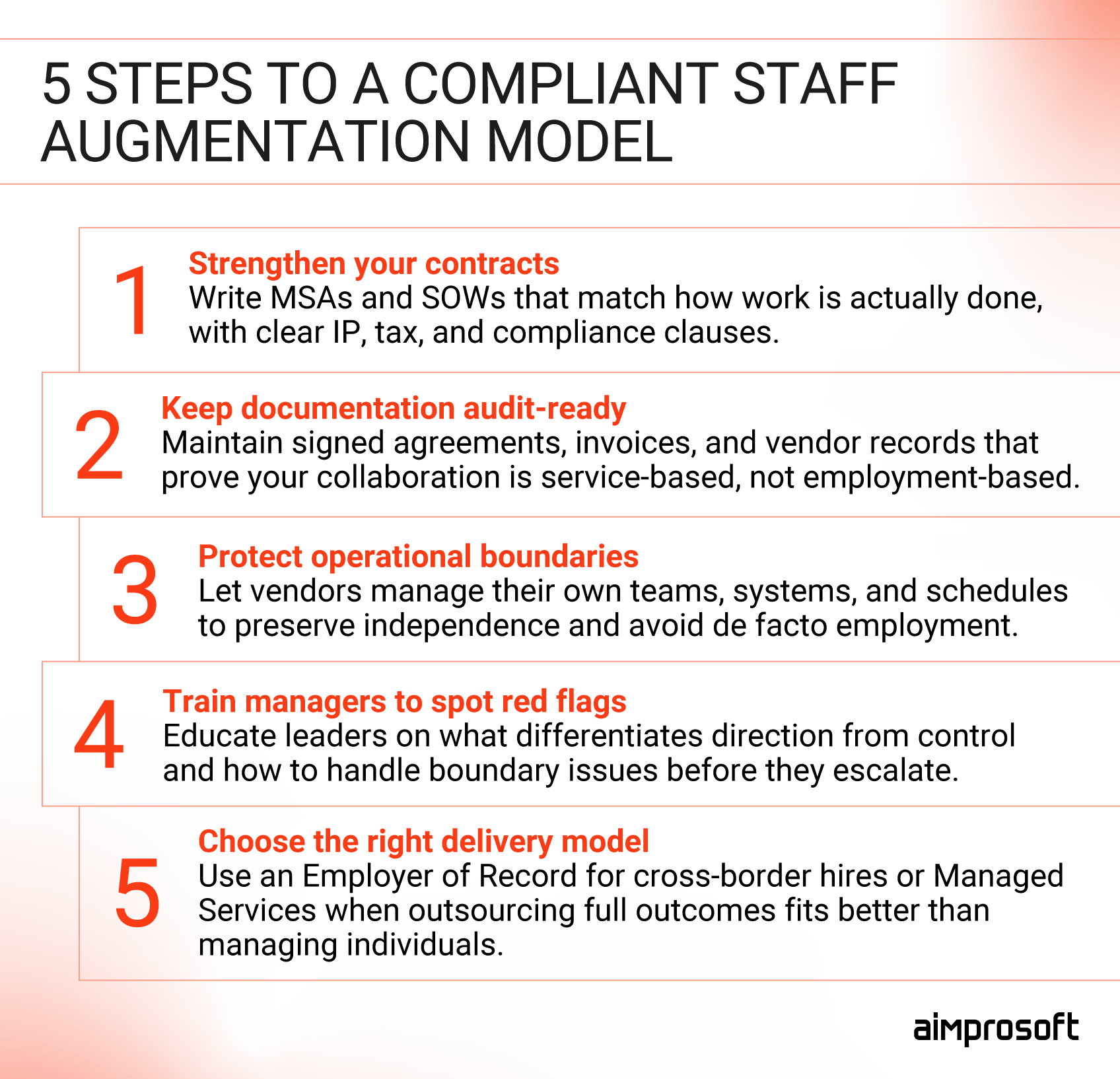

Building a compliant staff augmentation model

Preventing worker misclassification in tech outstaffing and co-employment risk comes down to structure, not complexity. When roles, supervision, and deliverables are clearly defined, demonstrating independence becomes easy for both auditors and regulators.

Compliance isn’t about slowing growth but about scaling safely, ensuring teams across regions operate within clear employment and tax boundaries. The following framework outlines the safeguards that keep staff augmentation agile, compliant, and audit-ready.

Strategic principles

Every sustainable compliance model starts with clarity at the strategic level. Before diving into specific measures, you need guiding principles that align teams, vendors, and leadership around a shared framework for accountability and control.

Transparency in engagement

Clarity is the foundation of safe collaboration. Every contributor’s role, reporting line, and scope of work should be visible and documented. When everyone, from project managers to vendor leads, understands who supervises what and who owns which deliverables, compliance becomes a natural outcome.

Governance and accountability

Strong governance keeps boundaries intact. Regular classification checks, access audits, and vendor performance reviews ensure that actual work practices match what’s written in contracts. Governance doesn’t slow teams down; it provides predictability and trust for both sides.

Cross-border alignment

As teams span multiple countries, the goal is consistency. Unified onboarding, security, and data-protection standards prevent gaps between regions. Shared templates and compliance procedures help every vendor team operate as part of the same transparent ecosystem.

Tactical implementation

Strategy only works when it’s visible in daily operations. These practical measures turn compliance principles into actions your teams can follow, across contracts, documentation, training, and delivery management.

1. Legal and contractual measures

Every compliant engagement starts with the paperwork. Contracts define the limits of the relationship, clarify accountability, and provide the first layer of defense during classification reviews. Clearly defined terms separate business-to-business collaboration from employment, protecting both sides from co-employment findings and misclassification claims.

Define scope and supervision clearly.

Each agreement should specify what the vendor delivers, who manages day-to-day work, and how progress is tracked. Avoid wording that implies employment, such as employee, salary, or reporting manager.

Include explicit IP and compliance clauses.

Master Service Agreements (MSAs) and Statements of Work (SOWs) should contain:

- IP assignment from vendor employees to the client

- Confirmation that the vendor handles taxes, payroll, and benefits

- Indemnity clauses if misclassification or co-employment is found

Use flow-down obligations. If the vendor works with subcontractors or freelancers, the same IP, confidentiality, and compliance clauses should extend automatically to them. This closes liability gaps in multi-tier delivery chains.

2. Documentation and transparency

Documentation connects intent with evidence. Without it, even the best structures are difficult to defend during audits. Proper records prove that vendor engineers operate independently rather than as shared employees.

Maintain clear paper trails.

Keep copies of MSAs, SOWs, invoices, and vendor registrations. These documents show that your collaboration is service-based, not employment-based.

Track contracts against reality.

Review whether working patterns match the agreements. Long-running projects may require updated SOWs or revised terms to reflect new scopes or responsibilities.

Implement classification reviews.

Conduct reviews at least once per year. In high-risk jurisdictions or for large contractor populations, increase the frequency to quarterly or semi-annual to stay ahead of regulatory changes. Early corrections are always cheaper than post-audit fixes.

3. Operational and structural safeguards

Day-to-day management is where co-employment risk surfaces most clearly. Even perfect contracts fail if the working reality looks like internal employment.

Separate management and HR processes.

External engineers should not participate in internal performance reviews, salary changes, or HR communications meant for employees. Their interaction should stay project-focused.

Limit integration and control.

Provide access only to tools and systems required for delivery. Avoid assigning company email accounts or including vendor staff in internal directories.

Work through a vendor’s delivery manager.

Let the vendor handle scheduling, task allocation, and performance management. This reinforces their role as a service provider rather than a labor supplier.

Duration and rotation considerations.

Monitor how long each contributor stays on the same project. Multi-year, full-time assignments can trigger employment tests in some regions. Rotate long-term roles or, when necessary, formally convert them to employment.

4. Training and communication

Awareness is the most effective compliance tool. Most co-employment and worker classification issues arise not from intent but from a lack of guidance.

Educate hiring managers and team leads.

Teach managers to focus on outcomes rather than methods. They should know how to collaborate with vendor teams without assuming employer responsibilities.

Establish escalation paths.

Set up clear channels to raise boundary concerns (e.g., if someone requests to include vendor staff in company-wide benefits or HR systems).

Refresh training regularly.

Include classification and compliance topics in new manager onboarding, and revisit them annually. Awareness at the team level keeps boundaries visible in daily operations.

5. Consider alternative engagement models

Sometimes reducing risk means changing the model altogether. Alternative structures can maintain flexibility while appropriately shifting compliance responsibilities.

Employer of Record (EOR). An EOR acts as the legal employer of record in another country, managing payroll, taxation, and labor compliance. This helps avoid misclassification and permanent establishment risks.

Managed services. For long-term or recurring functions, outsource outcomes instead of individuals. The vendor manages its own team and delivery process, while you measure results through service levels, not direct oversight. Both models reduce co-employment exposure by consolidating employment and management control under a single legal entity.

Embedding compliance into everyday operations

The best compliance models don’t rely on lawyers alone. They rely on shared responsibility: everyone from HR to engineering plays a part in keeping engagements clean and auditable. Once roles, metrics, and escalation paths are clear, compliance becomes part of how teams operate, not an occasional audit exercise.

1. Roles and responsibilities matrix

Defining who does what eliminates the gray zones that often lead to misclassification. You don’t need to hire new roles. Instead, you need to make ownership visible across the ones you already have.

- Legal: Reviews contracts, adds jurisdiction-specific clauses, and validates IP ownership language before signing.

- HR: Monitors how augmented staff are treated day-to-day. If external engineers start joining employee HR programs or internal evaluations, that’s a signal to adjust boundaries.

- Procurement: Tracks vendor renewals and ensures every new engagement includes updated compliance language.

- Engineering managers: Keep oversight operational, not managerial. Their role is to coordinate delivery, not direct how vendor engineers work.

Even in smaller organizations, one person can own multiple responsibilities. What matters most is that ownership is documented and communicated, rather than assumed.

2. Compliance metrics and KPIs

If you can’t measure it, you can’t maintain it. Metrics help you spot drift early and prove compliance when auditors ask questions. Start simple: focus on the areas that show whether your governance structure actually works. You should track:

- Contract accuracy: The percentage of current engagements with up-to-date MSAs, SOWs, and IP clauses.

- Vendor audit completion: How consistently you review vendor compliance and documentation.

- Response time: How long it takes to address a classification concern or contract discrepancy.

- Geographic readiness: Whether your company has coverage in every region where you engage talent, through an EOR, local entity, or verified partner.

These indicators give you more than reassurance; they provide evidence that your augmentation model can scale without introducing legal risk.

3. Escalation paths

Even well-structured engagements can drift. Someone adds a contractor to a team meeting, an engineer gets access to HR systems, or a project quietly extends for another year. Having a clear escalation process prevents small deviations from becoming compliance issues. Here’s how to set it up:

- Assign a single compliance contact. This could be your legal counsel, vendor manager, or project lead — the person responsible for assessing boundary risks.

- Define escalation triggers. Examples include unauthorized access, expired SOWs, or contractors being treated like employees.

- Create a resolution routine. Review the situation, correct the root cause (contract, process, or behavior), and document the change for audit readiness.

We can assist with software development, ensuring every process stays transparent, traceable, and globally compliant.

When everyone knows their role, understands what to measure, and has a clear way to flag concerns, compliance becomes second nature. The goal here is to create a rhythm where structure and agility support each other. That’s what keeps global staff augmentation stable, scalable, and audit-ready for the long term.

Wrapping up

Misclassification risks in staff augmentation rarely stem from bad intent. They start fast: teams scale quickly, boundaries blur, and documentation doesn’t keep pace. The result isn’t just a legal issue but an operational one: delayed releases, frozen budgets, and uncertainty over ownership. The companies that avoid these traps are the ones that treat compliance as part of delivery, not a separate staff augmentation compliance checklist.

A well-structured staff augmentation model makes independence visible at every level, from contracts and daily workflows to how teams report, document, and measure their engagements. That clarity protects your business, your IP, and the people who build your products.

If you’re scaling engineering capacity across borders, partner with a team that treats compliance as part of delivery. At Aimprosoft, we structure every engagement to stay transparent, audit-ready, and free from co-employment or misclassification risks, so you can focus on building products, not managing liabilities.

FAQ

What is misclassification in IT staffing?

Misclassification occurs when an individual hired as a contractor or vendor resource effectively works as an employee. In independent contractor classification IT scenarios, this often happens when external developers report directly to internal managers, use company systems, and follow the same schedule as full-time staff. Even if contracts label them as contractors, regulators assess real working conditions, not job titles. Such misclassification can result in tax, benefits, and compliance liabilities for both the vendor and the client.

What is the risk of co-employment in IT?

Co-employment in outstaffing risk arises when a company and a vendor share responsibility for the same worker. In IT, this typically occurs when augmented developers receive direction from the client’s managers while being paid by a vendor. The danger is that both parties may be viewed as joint employers, responsible for payroll taxes, benefits, and compliance obligations.

How to avoid misclassification when hiring globally?

When building distributed engineering teams, you should focus on structure and documentation. Each engagement must clearly define the scope of work, reporting lines, and payment terms that demonstrate independence. This helps prevent independent contractor misclassification risks, which often arise when day-to-day control doesn’t match what’s stated in contracts.

To strengthen global staff augmentation compliance, work through verified vendors, use Employer of Record (EOR) services when entering new jurisdictions, and perform regular classification reviews. The rule of thumb: ensure that the reality of the engagement always reflects what the contract describes.

How do I avoid co-employment in IT staffing?

Co-employment in IT staffing can be avoided by keeping management and employment functions separate. You should direct project outcomes but not handle HR tasks such as evaluations, benefits, or onboarding beyond the project context. All employment obligations should remain with the vendor, while you focus on deliverables and collaboration. Clear Master Service Agreements (MSAs), Statements of Work (SOWs), and communication protocols protect both sides from unintended joint-employment exposure

What are the penalties for misclassifying IT contractors?

Penalties vary by country, but they often include retroactive payroll taxes, unpaid social contributions, benefit compensation, and fines that can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars. In the U.S. and the EU, repeated violations can also trigger audits or restrictions on future contracting. Beyond financial costs, misclassification can disrupt funding rounds, delay product releases, and harm credibility with partners and employees. For companies focused on IT staffing legal compliance, staying proactive with documentation, periodic reviews, and transparent engagement structures is the most effective way to prevent these outcomes.

What are the main co-employment vs independent contractor risks in staff augmentation?

The biggest difference lies in control and accountability. When external specialists work under a client’s direct supervision, use its tools, and follow internal schedules, regulators may interpret the relationship as co-employment rather than independent contracting. That exposes both the vendor and client to shared payroll, tax, and benefit liabilities. True independent contractors, on the other hand, maintain business autonomy; they decide how and when to deliver outcomes, invoice directly, and handle their own taxes. Understanding where the line falls between independent contractor vs employee in IT roles is key to building compliant, scalable teams without crossing into unintended employment territory.