IT Staff Augmentation, Co-Employment & IP: The Definitive Guide for Tech Leaders

Published: – Updated:

When companies expand their engineering capacity through staff augmentation, they rarely think about co-employment or intellectual property at first. The goal is usually speed. A new product release. A quick scale-up. A chance to stay competitive without expanding headcount. Legal frameworks often enter the picture only when something goes wrong.

Over the past decade, as remote and cross-border teams became the new normal, these risks started to surface in ways many leaders hadn’t anticipated. Consider a scenario where a U.S. startup discovers that one of its augmented developers in another country technically co-owns part of the source code. Or imagine a European fintech facing a compliance review because its augmented engineers were classified as de facto employees. In both cases, the issue wasn’t bad intent. It was missing clarity.

Staff augmentation and IP ownership sit at the intersection of law, contracts, and everyday project management. They define who is legally responsible for a developer’s work, who owns what’s built, and what happens when that relationship ends. Yet most teams don’t discuss them until they have to untangle them. In this guide, we explore what co-employment in staff augmentation means, how IP ownership really works in distributed teams, and what practical steps you can take to stay protected. Our goal here is not to scare, but to prepare you to build global partnerships that are flexible, compliant, and risk-aware from day one.

What is co-employment in staff augmentation

At first glance, staff augmentation looks simple: you hire skilled professionals from a trusted vendor and manage them as part of your team. It feels efficient and flexible, though behind every engagement lies a legal structure that defines how responsibility is shared. One of those definitions is co-employment.

In practical terms, co-employment in IT happens when both your company and the vendor share some level of responsibility for the same worker. The developer may appear on the vendor’s payroll, yet their daily routine mirrors that of your internal team. To regulators (typically labor and tax authorities), that overlap can turn the vendor-client partnership into a joint employment relationship, where both parties may be held responsible for labor, tax, or benefit obligations.

In staff augmentation, co-employment often involves:

- External specialists integrated into internal workflows and communication tools.

- Direct supervision or feedback from your managers.

- Access to your company’s systems, credentials, and sometimes benefits.

- Shared responsibility for work direction, performance, or scheduling.

When several of these conditions exist together, the relationship begins to resemble employment, even if the contract says otherwise. This distinction separates staff augmentation from outsourcing (where the vendor manages delivery independently) and from independent contracting (where the individual controls how and when they work). Let’s examine how these models differ in practice.

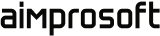

Co-employment vs. Independent contractor vs. Outsourcing

Understanding how co-employment in staff augmentation differs from other types of IT staffing models helps teams structure collaborations correctly.

Co-employment vs contractor vs outsoucring

Co-employment: shared responsibility and control

This model blends internal management with external employment. The augmented developers are on a vendor’s payroll, but they follow your internal processes, report to your managers, and often participate in company meetings or stand-ups. It offers flexibility and fast scaling, yet it also introduces shared accountability. If legal or compliance issues arise, both the vendor and you may be held liable by regulators, even if the contract attempts to limit that responsibility.

Typical indicators:

- Developers follow your daily instructions and priorities.

- Access to internal systems, repositories, or corporate communication channels.

- Ongoing collaboration that mirrors internal employment patterns.

When this level of integration occurs, regulators may view the relationship as joint employment rather than vendor collaboration.

Independent contractor: autonomy and deliverables

When comparing staff augmentation vs independent contractors, the main difference lies in how work is managed and who controls the process. Independent contractors operate as self-directed professionals, hired for specific outcomes rather than integrated into your daily operations. They manage their own tools, schedules, and workflows, often through their own legal entities.

This model minimizes co-employment risk but increases the need for clear deliverables and IP assignment clauses, since ownership of the work doesn’t automatically transfer to you.

Typical indicators:

- The contractor decides how and when to complete the work.

- Communication is limited to scope and deadlines, not daily oversight.

- The contractor issues invoices directly and handles their own taxes and benefits.

Outsourcing: managed delivery and limited visibility

In this case, you outsource a complete project or function to another company. The vendor is fully responsible for hiring, managing, and compensating its team. You measure progress through milestones or service-level agreements, not individual task control. This minimizes co-employment risk but reduces flexibility and visibility into individual performance.

Typical indicators:

- The vendor manages its own team internally.

- You interact mainly with a project or delivery manager.

- The relationship is defined by outcomes, not work methods.

These three models distribute legal responsibility, IP ownership, and compliance obligations differently. Staff augmentation offers a middle path, combining close collaboration with external flexibility, but this approach requires carefully defined boundaries to avoid co-employment risk.

Staff augmentation comes with unique legal and operational dynamics. If you’d like to learn more about how it compares to outsourcing and managed services, and why those distinctions matter for compliance and ownership, explore our detailed comparison.

What triggers co-employment

Co-employment doesn’t happen because of a single mistake. It emerges gradually when the relationship between a company and an augmented developer begins to resemble traditional employment. Regulators don’t rely on one rule or checklist. Instead, they evaluate the overall pattern of control, supervision, and dependency between the worker, the vendor, and the client. Several indicators tend to raise red flags:

- Direct control over daily work

When you set priorities, assign tasks, and manage performance reviews, it signals that the worker is functioning as an employee rather than an external contributor. - Integration into internal processes

Using company email accounts, participating in team meetings, or being listed in internal directories can make augmented staff appear indistinguishable from full-time employees. - Provision of tools and training

Supplying laptops, VPN access, or onboarding sessions designed for internal hires can also suggest an employer relationship, since your company is equipping and guiding the worker as if they were part of the core staff. - Duration and exclusivity

Long-term engagements with full-time schedules are harder to justify as independent collaboration. The longer the assignment lasts, the more likely regulators are to see it as a disguised employment relationship.

The interpretation of these signals varies significantly by region. In the United States, co-employment findings typically lead to payroll tax adjustments or retroactive benefit liabilities. In the European Union, the focus often shifts toward collective bargaining rights and data protection duties. In countries such as India or Brazil, investigations may revolve around taxation, permanent establishment, and vendor registration compliance.

For companies that rely heavily on augmented teams, recognizing these triggers early is critical. It’s not about limiting collaboration but about structuring it transparently, making sure that every role, responsibility, and contractual clause reflects how work is actually performed. Clear boundaries preserve agility while minimizing exposure to employment or IP disputes.

Wrapping up. Choosing the right model defines who controls the work, who owns the results, and who carries the legal responsibility if something goes wrong. Staff augmentation sits between the independence of contracting and the delegation of outsourcing, which is efficient for scaling but legally sensitive if boundaries aren’t clearly documented and maintained.

In the following section, we’ll explore how intellectual property rights are established in staff augmentation, why assumptions often fail, and how to secure ownership from day one.

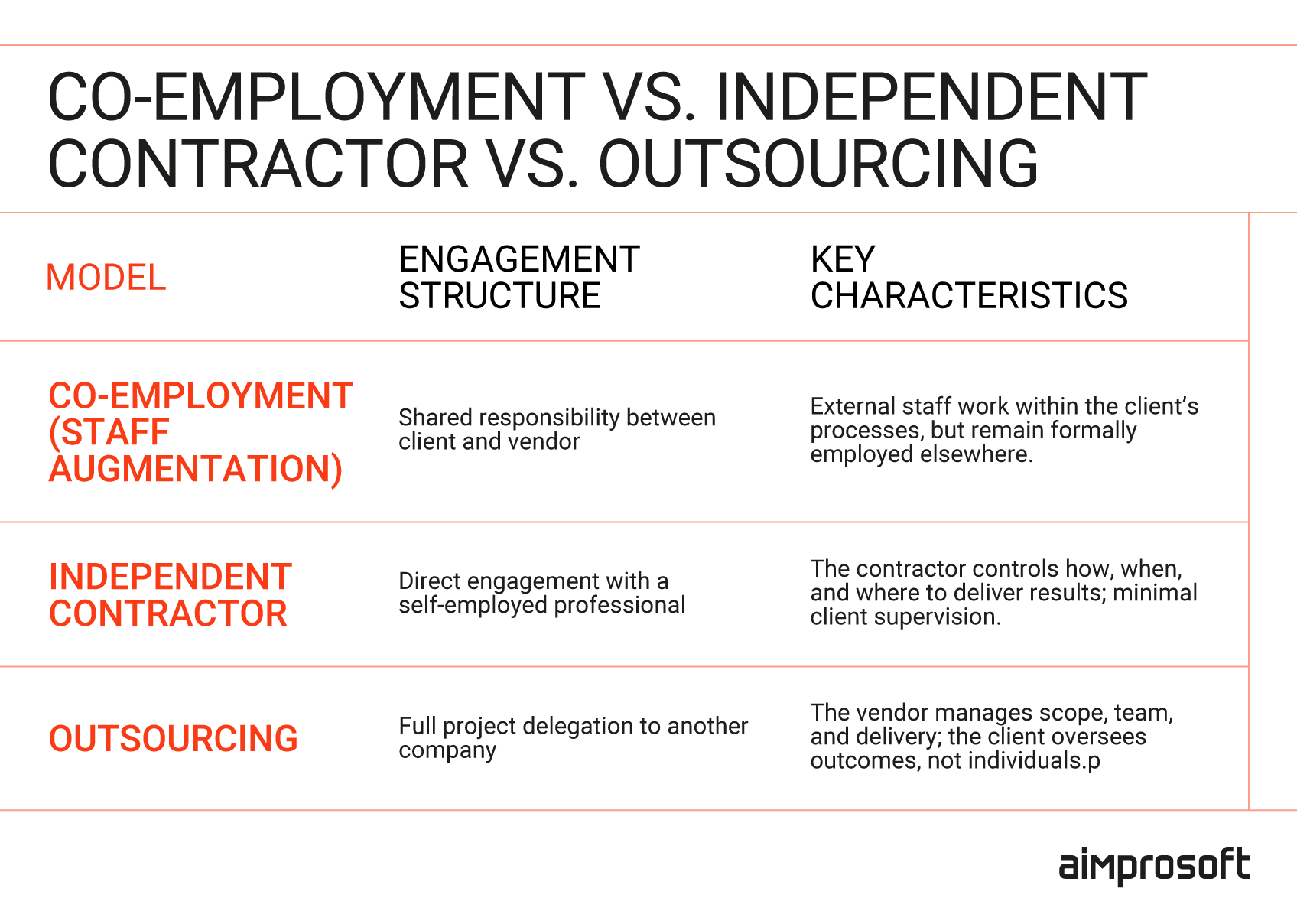

Who owns the code? Staff augmentation and IP ownership explained

When a company pays for software development, it’s easy to assume the finished product automatically belongs to them. In reality, intellectual property law doesn’t work that way. Payment grants the right to use the work, not always the right to own it. Ownership depends on how the staff augmentation vendor agreements define who creates, assigns, and controls the deliverables. Getting this right isn’t just legal housekeeping; it protects product continuity, valuation, and future scalability.

In staff augmentation, this distinction becomes even more important. Your augmented developers might be on someone else’s payroll, using their own hardware and accounts. Without proper assignment clauses, the code they produce can legally remain the property of their employer (or even of the individual developer) rather than your company.

IP ownership in staff augmentation

Common misconceptions about IP in staff augmentation

Many companies learn the difference between “use” and “ownership” only when a release is delayed, a client disputes rights, or an acquisition audit exposes missing documentation. Below are the most common assumptions that lead to IP uncertainty:

- “We paid for it, so we own it.”

Payment alone doesn’t transfer ownership. Without a written assignment, the developer or vendor may retain default rights under local law. - “It’s all our code.”

Augmented engineers often use frameworks, snippets, or tools that they or their company already owned before joining your project. Those elements may fall under the vendor’s “background IP” unless the contract defines how they can be reused. - “Open source means no restrictions.”

Public libraries come with licenses that may require attribution or restrict commercial use. Failing to track these can complicate future IP audits.

These misconceptions persist because most teams focus on delivery milestones, not legal architecture. Once you understand how ownership is transferred in law, you can protect your product before those risks appear.

Core legal concepts

Across jurisdictions, intellectual property ownership is structured through three main mechanisms: work-for-hire, assignment, and licensing.

- Work-for-hire applies primarily under U.S. law, where an employer automatically owns the work created by an employee. Outside the U.S., this model rarely applies, as most jurisdictions grant initial ownership to the creator, making a written IP assignment the essential step in transferring those rights to the client.

- IP assignment is a formal agreement that transfers ownership from the creator to the client. It’s the most reliable and universally recognized approach, especially when several vendors, subcontractors, or freelancers contribute to the same codebase.

- Licensing grants limited usage rights while ownership remains with the original creator. This model often applies when vendors use proprietary tools, frameworks, or libraries that support your product but aren’t fully transferred.

In staff augmentation, these distinctions decide who can legally use, modify, or commercialize your software after delivery, and why written assignment clauses should never be optional.

Background and foreground IP

Once ownership terms are clear, the next challenge is understanding what’s actually being owned. Every codebase mixes pre-existing and newly created intellectual property.

- Background IP includes existing assets: internal libraries, frameworks, and tools the vendor brings to the project.

- Foreground IP covers everything created during the engagement: new code, designs, or documentation funded by you.

When contracts fail to distinguish between them, background assets can accidentally end up bundled into your repository. Later, if you change vendors or commercialize the software, this mix can cause ownership disputes or licensing limitations.

A strong master service agreement (MSA) should spell out how background IP is used, how it’s licensed, and how the resulting product (the foreground IP) is transferred. Think of it as separating what powers your engine from what becomes your car.

When teams cross borders, risks multiply

Defining ownership is simple when everyone works in the same legal system. Add multiple countries, and the rules shift. Some jurisdictions assume the employer owns the IP. Others assign it to the individual developer until a written transfer occurs.

Imagine a European company working with an augmented team in South America. The vendor’s contract ensures IP transfer at the company level, but one developer operates as an independent contractor. If that person leaves before signing an assignment, part of the code may technically remain theirs. Situations like this have delayed funding rounds, product launches, and even M&A deals until missing agreements were corrected retroactively.

Cross-border cooperation is the norm in modern tech. But every added jurisdiction introduces another layer of IP complexity that needs written clarity, not verbal trust.

How to protect software intellectual property from day one

Protection of intellectual property in staff augmentation becomes manageable once you treat it as a process, not a last-minute formality. Clear documentation and precise contracts at the outset eliminate the legal cleanup that typically occurs later. Key practices to protect IP in global teams include:

- Explicit IP assignment clauses in MSA and SOW (statement of work), ensuring all vendor employees transfer ownership to you.

- Contributor acknowledgment forms for every developer, confirming their understanding of IP transfer obligations.

- An IP register that tracks which parts of the system rely on internal, vendor, or open-source components.

- Open-source license tracking to avoid compliance issues during audits.

- IP review checkpoints before major milestones or releases to confirm ownership of all deliverables.

We build partnerships where IP ownership, access control, and collaboration stay transparent and compliant from day one.

Handled proactively, intellectual property in IT transfer becomes routine, a quiet part of your process rather than an emergency before a launch or audit. Intellectual property defines the real value of your product. Thus, the clarity around intellectual property in staff augmentation is business protection, not just legal formality.

The earlier you establish who owns the code, the smoother every later decision becomes, from scaling development to entering new markets.

Legal and compliance blind spots in staff augmentation

Even when contracts look solid and vendor relationships run smoothly, hidden staff augmentation compliance risks can still surface. Most stem from three areas where assumptions often replace structure: worker classification, contractual clarity, and jurisdictional differences. Understanding these weak points early helps companies build more resilient vendor ecosystems.

Worker classification

One of the most common blind spots in staff augmentation is worker classification. When it’s unclear whether an augmented developer is an employee, contractor, or vendor staff member, regulators may interpret the setup as co-employment. The misclassification of contractors in staff augmentation can result in payroll liabilities, unpaid benefits, and retroactive tax obligations.

The difficulty lies in how differently countries define employment. What counts as independent in one jurisdiction may be employed in another. Regulators usually look at who directs the work, who provides the tools, and how deeply the worker is integrated into the client’s internal processes.

This topic deserves a closer look, which we’ll explore in the next article, including how different regions test for employment status and how to structure engagements that stay compliant without losing flexibility.

Incomplete or vague agreements

Even the best intentions fall apart without precise documentation. Missing or contradictory clauses are a recurring cause of both IP disputes and co-employment claims. When master service agreements and statements of work lack clear wording on ownership, supervision, or responsibilities, they leave enough room for interpretation to become liability. Common oversights include:

- No explicit IP assignment from vendor employees to the client.

- Undefined scope of supervision or reporting lines.

- Inconsistent contract language across multiple vendors or subcontractors.

- Silence on data access, security, and confidentiality obligations.

A short legal review at the start of an engagement costs less than a single audit letter later.

Jurisdiction-specific risks

Global compliance for IT teams’ rules differ widely between jurisdictions, and so do the consequences of getting them wrong. A policy that passes an audit in one country can raise red flags in another. Understanding these contrasts can help you shape contracts and operations that hold up across borders. Across regions, the focus of regulators tends to differ:

- United States: employment control and benefits.

Regulators often focus on payroll taxes, benefits, and worker classification. If augmented engineers work under direct client supervision, authorities may view it as co-employment. - European Union – Worker rights and data protection

Labor and privacy laws extend beyond full-time employees. Even vendor staff working within company systems can fall under collective bargaining or GDPR-related requirements. - India and Asia-Pacific – IP ownership and tax compliance

Authorities emphasize proper IP transfer, local registration, and taxation. Long-term control over offshore teams can create permanent establishment risk for the client company. - Latin America – Labor protection and enforcement

Strict employment laws and pro-worker courts mean misclassification or unpaid benefits can lead to severe penalties. Partnering with locally compliant vendors or EORs is often essential for risk mitigation.

Beyond these regional priorities, several recurring global patterns shape compliance exposure:

- Employment definitions vary. Some countries classify workers based on contractual independence, others on economic dependence or integration into company workflows.

- IP rights aren’t automatic. Without explicit transfer clauses, the creator or vendor may retain ownership by default.

- Data privacy now extends to third-party staff. Regions with strict data protection laws treat augmented engineers as potential data processors, bringing extra documentation and access control requirements.

- Enforcement can be unpredictable. Mature legal systems may audit less but penalize harder once violations are found. Emerging markets may audit more frequently but inconsistently.

For global organizations, compliance can’t be a fixed checklist. It’s a living framework that adapts to where teams operate, guided by local counsel and reinforced through regular audits and policy updates.

Wrapping up. Governments are paying closer attention to cross-border work structures than ever before. Increased enforcement, digital payroll audits, and coordinated labor inspections are now common in both mature and emerging markets. This doesn’t mean you should retreat from staff augmentation. It means you should approach it deliberately, with proper legal support and continuous policy reviews.

Staff augmentation compliance risks rarely explode out of nowhere. They build quietly, from an unclear clause, a missing signature, or a habit of managing augmented engineers as if they were full-time staff. Thus, the companies that handle augmentation well treat compliance as a design choice, not a reactive fix. They create frameworks that make legal safety invisible to developers but reliable to auditors.

The next step is to translate that mindset into action. In the following section, we’ll explore how to protect intellectual property and prevent co-employment from forming in the first place, covering everything from contract architecture to everyday operational practices that keep collaboration agile and compliant.

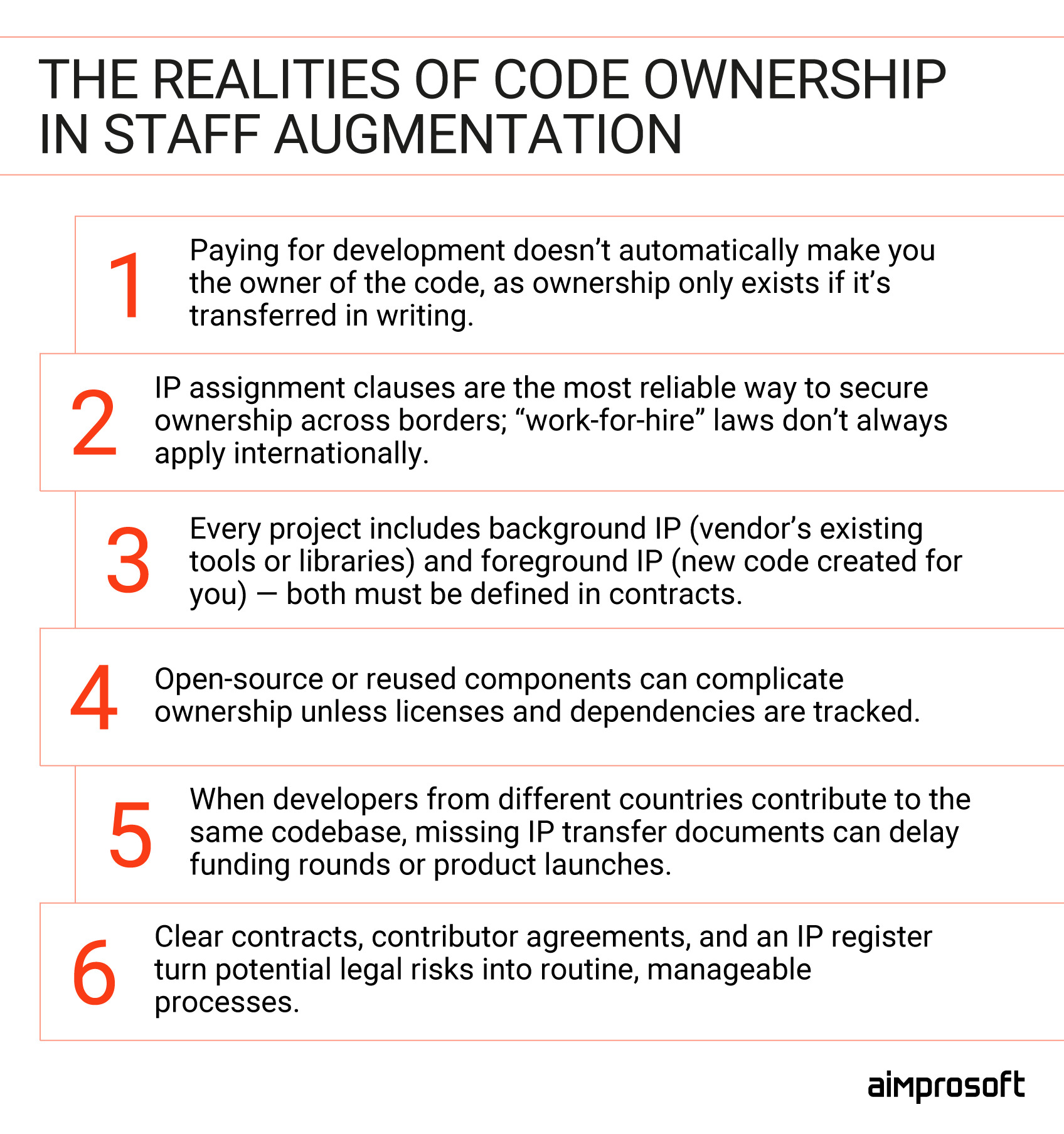

How to avoid co-employment and protect IP

After identifying co-employment risks in IT contracting, the next step is to design a structure that keeps ownership clear and relationships compliant. Protection doesn’t come from reactive legal interventions. It begins with intentional contract design and operational structure built into the engagement from day one.

How to avoid co-employment in staff augmentation

Contract structuring

Every safe collaboration starts with documentation that mirrors how work is actually done. A Master Service Agreement (MSA) sets the legal foundation: roles, payment terms, IP ownership, confidentiality, and liability. The Statement of Work (SOW) defines what the vendor delivers and under whose supervision. Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) protect sensitive data shared during collaboration.

When these documents are aligned, they form a complete legal picture, one that makes regulators, auditors, and investors confident in your operational discipline. Together, they prevent two recurring issues in IT contracting: unclear IP ownership and the kind of managerial overlap that can lead to co-employment findings.

Flow-down obligations

Contracts don’t end with your immediate vendor. If that vendor relies on subcontractors, freelancers, or nearshore partners, your protection must extend to them too. Flow-down clauses ensure that the same confidentiality, IP, data protection, and compliance obligations apply throughout the delivery chain. Without them, a subcontractor could retain partial IP rights or mishandle sensitive data without being directly accountable to you.

Embedding these obligations is about maintaining a consistent legal perimeter around your product. It ensures that everyone who contributes to your software operates under the same security and ownership standards.

Escrow and handover procedures

Even with solid contracts, unforeseen events can disrupt continuity: vendor bankruptcy, partnership termination, or sudden loss of key personnel. Source-code escrow agreements and detailed handover procedures act as insurance policies against such disruptions.

An escrow ensures that your company can access predefined critical assets if the vendor can no longer support the product. Handover documentation defines how code, credentials, and environments are transferred securely at the end of engagement. These measures transform dependency into resilience so that your business retains control even when external conditions change.

Indemnities and liability limits

No matter how carefully contracts are written, disputes and claims remain possible. Indemnity clauses define who bears responsibility if co-employment, IP infringement, or data breaches occur. They assign financial accountability to the party best positioned to prevent the issue.

Limitation of liability provisions, meanwhile, cap potential exposure to a manageable level, protecting both sides from unpredictable damages. These IP clauses in IT contracts promote trust: each party understands their boundaries and incentives for compliance.

Using an employer of record or managed services model

When companies need rapid expansion in unfamiliar jurisdictions, partnering with an Employer of Record (EOR) can simplify compliance. The EOR becomes the legal employer of record for augmented staff, handling payroll, taxation, and local labor obligations, while the client focuses on direction and performance. The EOR doesn’t manage delivery or performance but ensures local employment compliance.

Similarly, shifting from pure staff augmentation to a managed services model can reduce co-employment exposure. In this setup, you delegate outcomes instead of individuals. The vendor manages its own team, owns the process, and delivers results against defined service levels. It trades direct control for reduced liability, a delivery model that works best when scope and deliverables are clearly measurable.

Aimprosoft’s teams combine engineering expertise with clear ownership, security, and governance practices that protect your business as you scale.

Protection doesn’t come from paperwork alone. It comes from understanding how contracts, workflows, and governance reinforce each other. When companies build these protective layers deliberately, from contract design through handover procedures, they create an ecosystem where compliance is natural, not reactive.

The next section explores how to maintain that balance globally through governance, security, and continuous oversight, turning legal safety into a steady, scalable advantage.

Best practices for global staff augmentation

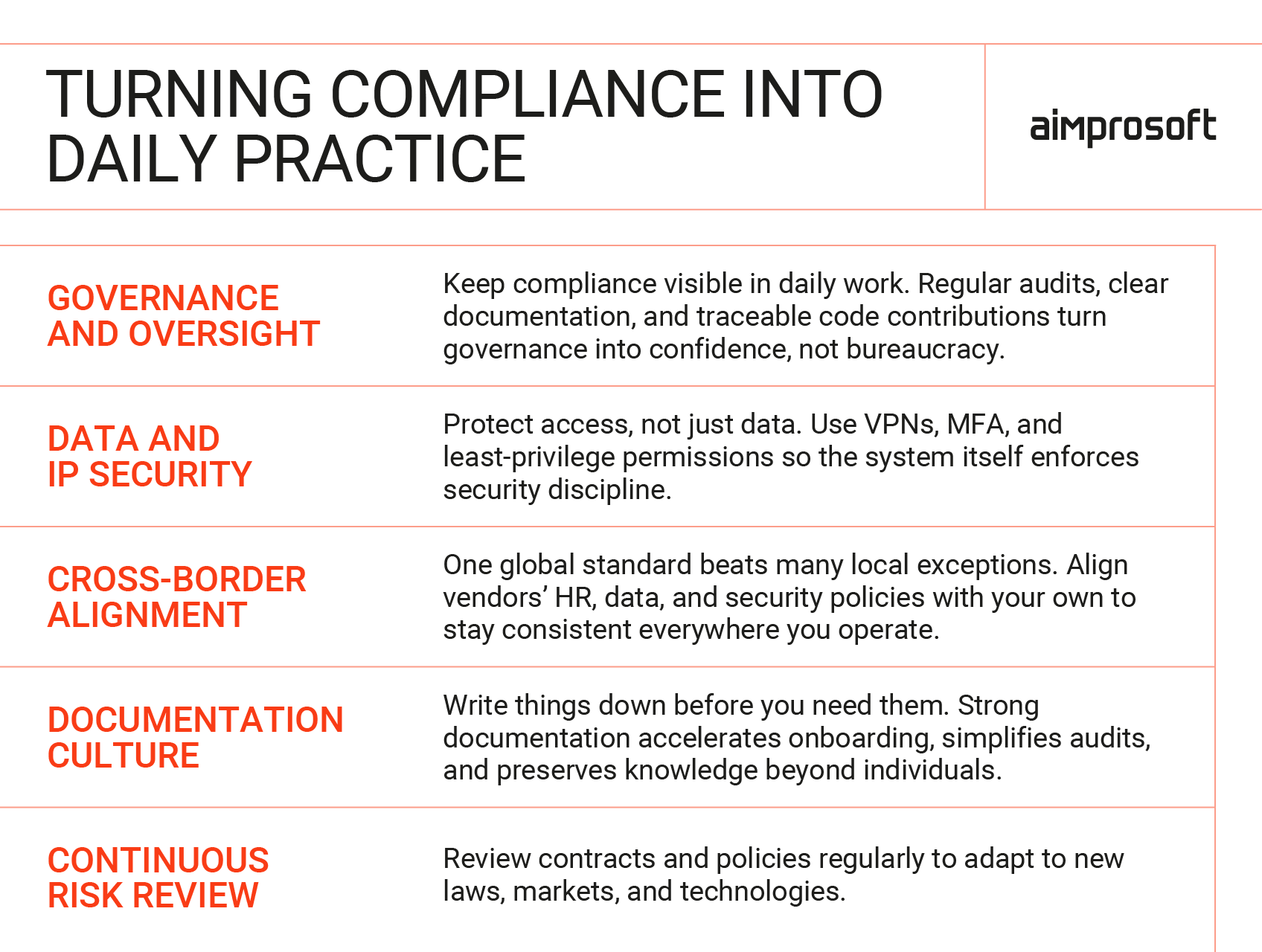

Legal clarity is only half the equation. The rest depends on how those agreements translate into everyday practice. Governance, security, and documentation turn compliance from a policy on paper into a living process that supports global delivery.

Best practices for global staff augmentation

Governance and oversight

Strong governance is the backbone of sustainable augmentation. It ensures that legal boundaries set in contracts remain visible in daily operations. Regular internal and vendor audits verify that team access, documentation, and data handling align with agreed standards.

Monitoring tools and version control systems make every code contribution traceable, while compliance documentation provides a clear paper trail for future reviews. Good governance doesn’t slow teams down; it gives them the confidence to move fast without creating hidden liabilities.

Data and IP security

In distributed environments, data protection and IP security go hand in hand. Each vendor or remote contributor becomes a potential access point to core business assets. Practical safeguards include VPN-based access, multi-factor authentication, and the least-privilege principle, where users only have access to what their role requires.

Secure repositories with detailed permission management prevent accidental exposure of sensitive code. Embedding these controls from the start reduces the need for constant policing; the system itself enforces good security behavior.

Cross-border alignment

Compliance loses value when internal and external teams operate under different standards. Aligning your vendors’ policies with your own HR, data protection, and security practices ensures that every team member (regardless of country) follows the same operational logic. This alignment can include shared onboarding modules, joint compliance training, or synchronized reporting templates. It also demonstrates to regulators and partners that the company applies one global standard rather than a patchwork of local exceptions.

Documentation culture

Documentation is the simplest and most overlooked form of risk management. Version control systems, structured onboarding guides, and transparent reporting make decisions traceable and responsibilities clear. A culture that prioritizes documentation preserves institutional knowledge and prevents misunderstandings during audits or transitions. Well-documented projects also help new augmented engineers integrate faster, reducing dependency on individual memory and informal communication.

Continuous risk review

Global staff augmentation compliance is not a static achievement; it’s a process that evolves with your team structure, jurisdictions, and technology stack. Regularly revisiting contracts, policies, and security protocols keeps them aligned with new regulations and business realities. Quarterly or biannual reviews, supported by legal and operational stakeholders, transform risk management from reactive to preventive. The goal isn’t to eliminate risk entirely but to make it visible, measurable, and controllable.

The most successful global teams combine legal precision with operational maturity. They treat governance, documentation, and security as part of the same ecosystem that protects both people and intellectual property. When these practices become routine, staff augmentation stops being a legal balancing act and becomes a reliable way to scale innovation across borders.

Wrapping up

Most companies discover risks of co-employment in staff augmentation only after a contract ends or an audit begins. By then, fixing the issue takes more time, money, and energy than preventing it ever would. Building clarity around IP, access, and governance early protects not just compliance but delivery speed and business continuity.

At Aimprosoft, we help partners expand engineering capacity across borders while keeping every aspect of collaboration, from code ownership to access control, transparent and secure. If you’re strengthening your global delivery model, let’s talk about building one that grows confidently, not cautiously.

FAQ

Does co-employment always mean a company has broken the law?

Not necessarily. Co-employment is a classification, not a violation. Problems arise only when the relationship isn’t structured or documented correctly. With clear contracts, separate HR processes, and a compliant vendor model, co-employment staffing services can be managed safely. Understanding and addressing co-employment risks in IT contracting early helps companies avoid penalties or reclassification later on.

How can I confirm that my company truly owns the code created by augmented developers?

Ownership must be confirmed through written IP assignment clauses in both the master agreement and the individual contributor contracts. You can also request confirmation from the vendor that every developer, including those engaged as co-employment IT contractors, has signed an internal IP transfer agreement. Without this full chain of documentation, your company may only hold usage rights, not full ownership.

What’s the difference between staff augmentation and outsourcing from a legal standpoint?

In staff augmentation, external specialists work within your processes and under your management, which can lead to co-employment risk if boundaries aren’t clear. In outsourcing, you contract an entire project or function to a vendor who manages their own staff and delivery. The distinction also affects intellectual property rights in software development, determining who legally owns the code, the deliverables, and ultimately who bears responsibility for both the people and the results.

When should a company consider using an Employer of Record (EOR)?

An EOR is especially useful when you need to hire talent in a country where you don’t have a legal entity. The EOR becomes the official employer, managing payroll, taxes, and local labor law compliance. This model helps companies scale globally without taking on direct employment risk or the staff augmentation legal risks that often arise when contracts, responsibilities, and compliance boundaries aren’t clearly defined.

What’s the most common mistake companies make with staff augmentation contracts?

The most frequent issue is assuming that a single MSA or generic vendor agreement covers everything. In reality, each project requires a clearly defined scope, supervision model, and IP assignment process. Many companies overlook who owns IP in staff augmentation, leaving ownership terms vague or undocumented, which can create problems later. Skipping these details often leads to blurred responsibilities, unclear ownership, and even co-employment risks in IT contracting during audits or acquisitions.